Lessons From Other Media

I've found that if I give myself time to percolate an idea, it never ends up getting posted. So here's something I started writing about the games and art thing, more focused on what we can learn about formal design elements than debating what art is or isn't. I think it comes off a bit snotty in places, so be warned. I'll probably continue this as a series exploring some parallels between different media as I come across them.

After a few years majoring in fine art in college and a few years as a game designer, my definition of art is as follows:

An idea intentionally expressed through a medium.

There. Pretty simple.

This, of course, includes games. I don't think I have to convince you, if you're reading this, that our medium is a valid form of artistic expression. You get it, and if not I'm probably not going to convince you here. The whole what is/isn't art conversation has served as pretentious lip fodder at parties well before video games came around anyway, and what interests me as a designer is what makes good art.

There are good and bad examples to be seen in every medium, from Mozart to the latest corporate spawned pop drivel, from Kandinsky to Kinkade. What separates the chaff from the wheat is the potency (and honesty) of the message combined with the skillful use of formal elements. These formal elements, like visual design principles or the interactions of game mechanics, act as amplifiers that can make the message speak louder. If they are used improperly, however, they can drown the message in white noise or negate it entirely (hello, dissonance). In some cases, this can be a fairly one sided equation. The message can be so powerful that little executive finesse is required for it to speak to an audience. On the flip-side some purely concrete works (Mondrian, Tetris) stand solely on their formal merits, where their messages are a sort of meta-expression about themselves and nothing more.

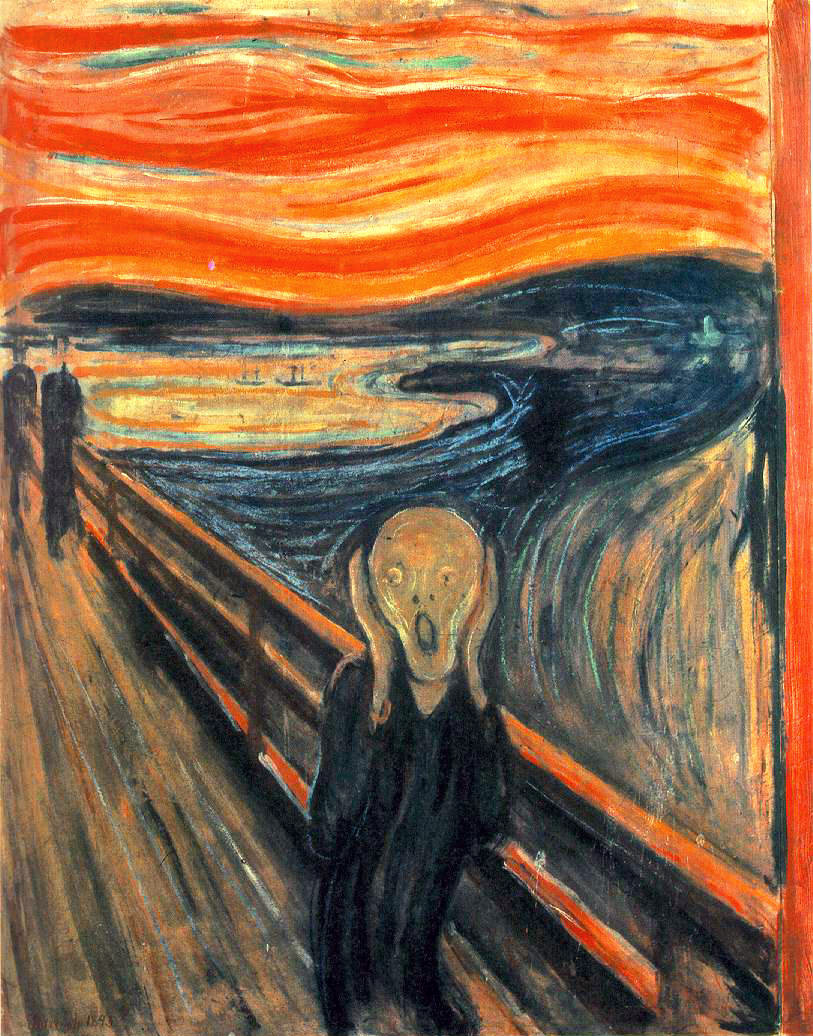

I think some tried and true lessons from the visual medium could offer us some insight in the interactive field. Let's take something like Munch's The Scream as an example.

Ripped straight from Wikipedia, Munch's inspiration for the painting:

"I was walking along a path with two friends—the sun was setting—suddenly the sky turned blood red—I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence—there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city—my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety—and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature."

The article then goes on to postulate what could have made the sky red, or whether or not Munch was being literal or expressive, etc. I think this might be useful for an academic studying some sort of contextual or historical positioning of the work, but for the end user, the observer, all of this is useless. You can't expect deep resonance from a work that relies on someone standing in front of it to explain each brushstroke. The aesthetic message has to hit the viewer through the power of the image. That's why it's a painting and not a novella.

When the viewer first looks at The Scream he gets that message immediately, like a shotgun blast. Munch achieves this with several tools. The first couple of things are sort of narrative, contextual supports.

Title

First, the name itself sets up a preconceived expectation in the viewer. This seems like a pretty obvious concept, but I think it's worth noting just to be thorough. When someone says, "Let's go look at 'The Scream'", you psychologically set yourself up for something nerve wracking. The same thing goes for an interactive experience. If a game is called "Blood Dungeon" and you start out in a field full of bunnies, you're going to constantly be expecting things to go to hell at some point. This can be used to reinforce a mood or establish it prior to the user's exposure. Alternately this can be used to put the user on uneven footing by giving vague or contrary information. Part of using a formal system is knowing when to subvert it.

Subject Matter

Next is the subject matter. Again, this is narrative and contextual and not necessarily a formal element. Formality vs narrative has been a prevalent issue in fine art just as much as it has in games. Personally, I don't see the story versus gameplay debate as a rift between opposing factions as much as ludo-narrative axes that can be expressed orthogonally. In the case of The Scream, the screaming person in the foreground can't be ignored as an agent of emotional impact, a conduit of the message.

Now on to the formal elements, the properties of the work that are native to the medium.

Nervous Marks

The very nature of the gestural marks in the work depicts a nervous sense of motion, vibration almost. You can feel the artist's hand as he put down the marks with his brush. The whole thing is organic and undulating with few spaces for the eye to rest calmly. If you look at the bridge, however, you'll find more stable linear elements, but these serve mainly to make the wavy marks look even more wavy in contrast. Pushing agents like this can accentuate the qualities of contrasting elements if they're used in the right proportions.

Distortions

The figures and palette of this piece aren't very naturalistic at all. The people are recognizable enough to sort of resonate with your empathic core, but are distorted to create a great sense of unease. The contortions look terribly uncomfortable, and part of us can empathize and feel that discomfort as well. The palette is a departure from reality as well, with the reddish orange color taking a prominent role. This is not just an unusual color for the sky, but a very aggressive color as well. Add in the blues and greenish hues and more vibration is added through simultaneous contrast.

In games we have complete control over the laws of nature. If we want to empower the player, we can make him jump yards into the air or run 100 miles an hour. If we want to invoke helplessness we can slow him to a crawl or make him fragile. We are, after all, giving simulations opinions here, so our every physical formula is an expression on how we want our micro worlds to be.

Graphic Elements

By graphic I'm referring to flat 2d elements, not images on a screen In addition to the emotionally charged elements, there are forces at work to ensure the work remains graphic, flat, embedded in the picture plane. The background is a warmer color, so it advances, negating depth. The whole thing is permeated by a reddish ground color, which holds it all together. There's no modeling of shadow or highlight throughout the work. The perspective lines also fall along structural format lines, rooting them more in the 2d plane than a depiction of 3d space.

For a 2d work to effectively engage a viewer, it has to play to its strengths, the 2d plane. Graphic elements like I mentioned above can reinforce the 2d nature of a work and cause the viewer to engage it as shapes on a plane rather than illustrative simulacra. Linear perspective is an artificial system that is used to evoke space, but the sight lines can be combined with structural lines or subverted in other image-serving ways to negate space while still sort of 'referring to' it. Kind of having your cake and eating it too, but it's all a matter of knowing the rules and how to bend them.

I believe this and other photo-realistic attempts at art correspond pretty closely to the holy grail of simulatory verisimilitude in games. Even at the highest fidelity of rendering, a 2d work is still abstract. The image is flat while the subject matter is three dimensional. The palette won't be 100% accurate. If you magnify the work, you won't be able to see cells, molecules, etc. Yes, this is a bit obvious but the point is that you have to stop somewhere in your depiction of reality, and that's where the designer's voice can be found. I think that you can give the player the feeling of depth and choice without trying to turn the map into the territory.

That's a rough pass on some of my thoughts about art and the interactive medium. As usual, I don't think I'm handing down some sort of gospel as much as opening a dialogue and presenting ideas to be refined through feedback. There aren't really any specific game examples in this installment, but I might revisit the concept with some examples from the interactive side of things. This might just end up being a rehash of the MDA framework with some visual art parallels, however.

After a few years majoring in fine art in college and a few years as a game designer, my definition of art is as follows:

An idea intentionally expressed through a medium.

There. Pretty simple.

This, of course, includes games. I don't think I have to convince you, if you're reading this, that our medium is a valid form of artistic expression. You get it, and if not I'm probably not going to convince you here. The whole what is/isn't art conversation has served as pretentious lip fodder at parties well before video games came around anyway, and what interests me as a designer is what makes good art.

There are good and bad examples to be seen in every medium, from Mozart to the latest corporate spawned pop drivel, from Kandinsky to Kinkade. What separates the chaff from the wheat is the potency (and honesty) of the message combined with the skillful use of formal elements. These formal elements, like visual design principles or the interactions of game mechanics, act as amplifiers that can make the message speak louder. If they are used improperly, however, they can drown the message in white noise or negate it entirely (hello, dissonance). In some cases, this can be a fairly one sided equation. The message can be so powerful that little executive finesse is required for it to speak to an audience. On the flip-side some purely concrete works (Mondrian, Tetris) stand solely on their formal merits, where their messages are a sort of meta-expression about themselves and nothing more.

I think some tried and true lessons from the visual medium could offer us some insight in the interactive field. Let's take something like Munch's The Scream as an example.

Ripped straight from Wikipedia, Munch's inspiration for the painting:

"I was walking along a path with two friends—the sun was setting—suddenly the sky turned blood red—I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence—there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city—my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety—and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature."

The article then goes on to postulate what could have made the sky red, or whether or not Munch was being literal or expressive, etc. I think this might be useful for an academic studying some sort of contextual or historical positioning of the work, but for the end user, the observer, all of this is useless. You can't expect deep resonance from a work that relies on someone standing in front of it to explain each brushstroke. The aesthetic message has to hit the viewer through the power of the image. That's why it's a painting and not a novella.

When the viewer first looks at The Scream he gets that message immediately, like a shotgun blast. Munch achieves this with several tools. The first couple of things are sort of narrative, contextual supports.

Title

First, the name itself sets up a preconceived expectation in the viewer. This seems like a pretty obvious concept, but I think it's worth noting just to be thorough. When someone says, "Let's go look at 'The Scream'", you psychologically set yourself up for something nerve wracking. The same thing goes for an interactive experience. If a game is called "Blood Dungeon" and you start out in a field full of bunnies, you're going to constantly be expecting things to go to hell at some point. This can be used to reinforce a mood or establish it prior to the user's exposure. Alternately this can be used to put the user on uneven footing by giving vague or contrary information. Part of using a formal system is knowing when to subvert it.

Subject Matter

Next is the subject matter. Again, this is narrative and contextual and not necessarily a formal element. Formality vs narrative has been a prevalent issue in fine art just as much as it has in games. Personally, I don't see the story versus gameplay debate as a rift between opposing factions as much as ludo-narrative axes that can be expressed orthogonally. In the case of The Scream, the screaming person in the foreground can't be ignored as an agent of emotional impact, a conduit of the message.

Now on to the formal elements, the properties of the work that are native to the medium.

Nervous Marks

The very nature of the gestural marks in the work depicts a nervous sense of motion, vibration almost. You can feel the artist's hand as he put down the marks with his brush. The whole thing is organic and undulating with few spaces for the eye to rest calmly. If you look at the bridge, however, you'll find more stable linear elements, but these serve mainly to make the wavy marks look even more wavy in contrast. Pushing agents like this can accentuate the qualities of contrasting elements if they're used in the right proportions.

Distortions

The figures and palette of this piece aren't very naturalistic at all. The people are recognizable enough to sort of resonate with your empathic core, but are distorted to create a great sense of unease. The contortions look terribly uncomfortable, and part of us can empathize and feel that discomfort as well. The palette is a departure from reality as well, with the reddish orange color taking a prominent role. This is not just an unusual color for the sky, but a very aggressive color as well. Add in the blues and greenish hues and more vibration is added through simultaneous contrast.

In games we have complete control over the laws of nature. If we want to empower the player, we can make him jump yards into the air or run 100 miles an hour. If we want to invoke helplessness we can slow him to a crawl or make him fragile. We are, after all, giving simulations opinions here, so our every physical formula is an expression on how we want our micro worlds to be.

Graphic Elements

By graphic I'm referring to flat 2d elements, not images on a screen In addition to the emotionally charged elements, there are forces at work to ensure the work remains graphic, flat, embedded in the picture plane. The background is a warmer color, so it advances, negating depth. The whole thing is permeated by a reddish ground color, which holds it all together. There's no modeling of shadow or highlight throughout the work. The perspective lines also fall along structural format lines, rooting them more in the 2d plane than a depiction of 3d space.

For a 2d work to effectively engage a viewer, it has to play to its strengths, the 2d plane. Graphic elements like I mentioned above can reinforce the 2d nature of a work and cause the viewer to engage it as shapes on a plane rather than illustrative simulacra. Linear perspective is an artificial system that is used to evoke space, but the sight lines can be combined with structural lines or subverted in other image-serving ways to negate space while still sort of 'referring to' it. Kind of having your cake and eating it too, but it's all a matter of knowing the rules and how to bend them.

I believe this and other photo-realistic attempts at art correspond pretty closely to the holy grail of simulatory verisimilitude in games. Even at the highest fidelity of rendering, a 2d work is still abstract. The image is flat while the subject matter is three dimensional. The palette won't be 100% accurate. If you magnify the work, you won't be able to see cells, molecules, etc. Yes, this is a bit obvious but the point is that you have to stop somewhere in your depiction of reality, and that's where the designer's voice can be found. I think that you can give the player the feeling of depth and choice without trying to turn the map into the territory.

That's a rough pass on some of my thoughts about art and the interactive medium. As usual, I don't think I'm handing down some sort of gospel as much as opening a dialogue and presenting ideas to be refined through feedback. There aren't really any specific game examples in this installment, but I might revisit the concept with some examples from the interactive side of things. This might just end up being a rehash of the MDA framework with some visual art parallels, however.

Labels: art, game design